Tuesday, August 27, 2013

Living on Everyday Prayers: David Burton ‘88

By Sarah Lee

Drury University Alumni Magazine

For some people, making a “life plan” is a no brainer. Some people know

exactly what they want to do with their lives so they make plans in order to

achieve their goals. But what about the rest of us who don’t know what the

future holds? What about those who take it day by day until they can find a

true calling? Well, you’ll be glad to know that you are not alone.

“I don’t make too many concrete plans,” David Burton, explains, “Some

folks have a life-long calling, and I’d like to think that my calling is just

day to day.” Burton is a civic communication specialist for University of

Missouri Extension. He graduated from Drury in 1988 with a degree in political

science and communication/journalism, and then again in 2001 for his master’s

degree in communication. He is currently the author of three books and two

online blogs. In his latest book, “Prayers for My Public School,” Burton

provides readers with a chance to think about prayer on a day to day basis.

“It’s a Facebook page in print,” Burton explains when asked to describe

the book, “I started a page back in 2010 called, ‘Pray for the Republic School

District,’ and I just made a commitment to post a prayer on the page each day.

After doing that for several years, my wife said that I should write it down

and compile it into a book. The meat of the book consists of prayers broken up

by day. The Facebook page is still going. I’m just trying to get everyone in

the habit of praying every day.”

For David, prayer is an important practice that he believes will

provide guidance and encouragement. He believes that God can take small actions

– such as praying on a daily basis – and help them to make a big impact.

Thanks for really caring

News-Leader

Opinion Page

August 27, 2013

Thanks for really caring

Good news is not hard to find in the Ozarks, as we illustrate regularly with an editorial feature we call: ‘Tis a privilege.

’Tis a privilege to celebrate and salute more than 1,700 volunteers who took part in Thursday’s United Way of the Ozarks Day of Caring.

Volunteers from 96 companies and organizations took part in the 21st annual event, providing muscle and energy and creativity to help address needs in Springfield and Greene County, as well as Taney and Polk counties. Volunteers worked on 155 projects for 55 nonprofits.

’Tis a privilege to thank the anonymous donor who answered the prayers of Father Joseph McCormack — providing him with a new scooter to replace one stolen a few days earlier. McCormack, a monk with the Eastern Orthodox Church, relies on the scooter to visit hospitals and convalescent homes, delivering quilts for the Healing Quilt Project of the Ozarks. After a story was published Aug. 17, several community members responded and one from Aurora provided the replacement.

’Tis a privilege to encourage walkers everywhere, and to thank our local hospitals, Mercy and CoxHealth, on the joint effort to create the Medical Mile Trail between the two hospitals. The 5.6 mile walking path, including side trails, was dedicated Saturday. Walking is one of the easiest and best forms of exercise. See you on the trail!

’Tis a privilege to acknowledge David Burton for his oneman effort to keep alive the memories of one-room schools in Greene County and the Ozarks. Burton, communication specialist with the University of Missouri Extension-Greene County, has written two books on the subject. One is a history of local schools and the other is driving tour — perfect for a Labor Day weekend road trip.

’Tis a privilege to thank Springfield firefighters for putting their lives on the line every day — but also for the extra efforts they make to help keep our community safe. Firefighters will soon begin annual visits to schools, teaching fire safety tips to more than 4,000 children. As a bonus, every child will get a pack of crayons and an activity book to complete at home, including a home escape plan. Books were donated by courtesy of Paragon Architecture and the Sertoma Club.

’Tis a privilege to remember Paul Nahon, a former Glendale High tennis champion who was admired by many as a role model for his passion for life, as well as academic and other accomplishments. Nahon was remembered Saturday at memorial services. He died Aug. 15 after a 150-foot fall while attempting to climb Longs Peak in Colorado.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

In Search of One-Room School Houses

From the Springfield News-Leader

Printed Aug. 22, 2013

Written by Juliana Goodwin

In 1918, in a one-room schoolhouse in Ash Grove, Orlis Farmer watched his teacher get in a fistfight with an older student.

The battle lasted an hour and left blood on the snow.

It made enough of an impression on little Orlis that when he grew up, he would tell the story to his grandson, David Burton.

That story and others sparked an interest in Burton about one-room schoolhouses, which he began researching in 1998.

“The schoolhouse is important in the same way a battlefield is important for war history. Having the school helps you tell that historical story,” Burton said. “It’s tangible. It’s important to catalog them.”

Initially, Burton thought he was settling in for a weekend project locating remaining schoolhouses in Greene County.

Fifteen years later, his research is complete, and he has written two books on the subject..

“The books have been a labor of love and a hobby that got out of hand,” said Burton, who is the communication specialist with the University of Missouri Extension-Greene County. He also founded the Missouri Historical Schools Alliance and is on the board of directors for the Country School Association of America.

Many were white

When people think of one-room schoolhouses, many think of the “iconic little red schoolhouse” native to New England, but that’s not typical in Missouri. Many were white, and often they were constructed with whatever materials were available.

“One was made of fieldstones. The Willey Brothers had a lumber mill, so the Willey School was well constructed. My favorite is the brick schoolhouse creatively called the Brick Schoolhouse,” Burton said.

In 1998, he started extensively researching schoolhouses around the Ozarks.

There were many challenges. When he started, he had no idea how many schoolhouses there were.

In 1905, Missouri passed the compulsory school attendance law requiring children ages 8 to 14 to attend school for at least three-fourths of the school term.

By 1906, there were 124 school districts in Greene County.

“It took some legwork and researching and traveling,” said Burton.

While there were old maps of the schoolhouses, the maps weren’t always accurate.

From 1869 to 1950, about 75 percent of all one-room schoolhouses in Greene County burned because of stoves, coal, lanterns and lightning, Burton learned.

Of those that survived, some had been moved or converted, and some had fallen into disrepair. Sometimes the roads leading to the schools had disappeared.

When Burton tried to take his grandmother back to her one-room schoolhouse, it wasn’t there, but her memory was correct about where it was. It turns out the roads had changed, so they couldn’t find it.

One clue he’d look for in uncovering a schoolhouse was a disproportionate number of windows on one side of the building.

Children were taught to write with their right hands, so the idea was that sunlight should come from the left side of the building so that it wouldn’t cast shadows on the paper and potentially affect children’s vision. Therefore, many schools have a lot of windows or large windows on one side of the building but not on the other.

Knowing this helped him on his quest to put together the book.

Once, he spotted a barn with big windows on one side only and asked the farmer about it because Burton thought maybe it had been a schoolhouse at one time.

It had been.

“He said no one has asked me about that in a long time,” Burton said.

Social hub

Not only did the one-room schoolhouse play an important role in Missouri’s education system, it was vital in each community and often was a gathering spot for ice cream socials and other community events.

Teachers in these schools were young, and many were male to better deal with rowdy, older farm boys.

Teachers’ salaries were tied to how well they did on a state test. The better they scored, the higher their pay. In order to get a raise, they could retake the test, and if they scored higher, they could get a pay increase.

In Greene County, the one-room schoolhouse died out from 1951 to 1954, when most schools consolidated.

By the 1950s, roads were good enough that children could be bused to school, and the expectations of what an education should be had changed.

“The original mission of the one-room schoolhouse was to bring literacy and writing to rural America,” Burton said. “That mission was accomplished with flying colors, but as society changed, that changed.”

Communities voted on school districts with which they wanted to consolidate. Much like an election year, people went door to door trying to sell their neighbors on a particular district.

As the schoolhouses closed, some were sold at auction, turned into barns, moved, destroyed or abandoned.

But as Burton has worked on this over the years, he’s found an increasing number of people are realizing the importance of preserving what history is left, which is heartening.

For example, Texas County has a historic driving tour of one-room schoolhouses.

“There seems to be a resurgence of interest in preserving the one-room schoolhouse,” he said. “That’s encouraging. There’s a lot that can be learned from the older generation about community, family and what it meant to be educated in a one-room schoolhouse. This has been a fun project.”

Printed Aug. 22, 2013

Written by Juliana Goodwin

In 1918, in a one-room schoolhouse in Ash Grove, Orlis Farmer watched his teacher get in a fistfight with an older student.

The battle lasted an hour and left blood on the snow.

It made enough of an impression on little Orlis that when he grew up, he would tell the story to his grandson, David Burton.

That story and others sparked an interest in Burton about one-room schoolhouses, which he began researching in 1998.

“The schoolhouse is important in the same way a battlefield is important for war history. Having the school helps you tell that historical story,” Burton said. “It’s tangible. It’s important to catalog them.”

Initially, Burton thought he was settling in for a weekend project locating remaining schoolhouses in Greene County.

Fifteen years later, his research is complete, and he has written two books on the subject..

“The books have been a labor of love and a hobby that got out of hand,” said Burton, who is the communication specialist with the University of Missouri Extension-Greene County. He also founded the Missouri Historical Schools Alliance and is on the board of directors for the Country School Association of America.

Many were white

When people think of one-room schoolhouses, many think of the “iconic little red schoolhouse” native to New England, but that’s not typical in Missouri. Many were white, and often they were constructed with whatever materials were available.

“One was made of fieldstones. The Willey Brothers had a lumber mill, so the Willey School was well constructed. My favorite is the brick schoolhouse creatively called the Brick Schoolhouse,” Burton said.

In 1998, he started extensively researching schoolhouses around the Ozarks.

There were many challenges. When he started, he had no idea how many schoolhouses there were.

In 1905, Missouri passed the compulsory school attendance law requiring children ages 8 to 14 to attend school for at least three-fourths of the school term.

By 1906, there were 124 school districts in Greene County.

“It took some legwork and researching and traveling,” said Burton.

While there were old maps of the schoolhouses, the maps weren’t always accurate.

From 1869 to 1950, about 75 percent of all one-room schoolhouses in Greene County burned because of stoves, coal, lanterns and lightning, Burton learned.

Of those that survived, some had been moved or converted, and some had fallen into disrepair. Sometimes the roads leading to the schools had disappeared.

When Burton tried to take his grandmother back to her one-room schoolhouse, it wasn’t there, but her memory was correct about where it was. It turns out the roads had changed, so they couldn’t find it.

One clue he’d look for in uncovering a schoolhouse was a disproportionate number of windows on one side of the building.

Children were taught to write with their right hands, so the idea was that sunlight should come from the left side of the building so that it wouldn’t cast shadows on the paper and potentially affect children’s vision. Therefore, many schools have a lot of windows or large windows on one side of the building but not on the other.

Knowing this helped him on his quest to put together the book.

Once, he spotted a barn with big windows on one side only and asked the farmer about it because Burton thought maybe it had been a schoolhouse at one time.

It had been.

“He said no one has asked me about that in a long time,” Burton said.

Social hub

Not only did the one-room schoolhouse play an important role in Missouri’s education system, it was vital in each community and often was a gathering spot for ice cream socials and other community events.

Teachers in these schools were young, and many were male to better deal with rowdy, older farm boys.

Teachers’ salaries were tied to how well they did on a state test. The better they scored, the higher their pay. In order to get a raise, they could retake the test, and if they scored higher, they could get a pay increase.

In Greene County, the one-room schoolhouse died out from 1951 to 1954, when most schools consolidated.

By the 1950s, roads were good enough that children could be bused to school, and the expectations of what an education should be had changed.

“The original mission of the one-room schoolhouse was to bring literacy and writing to rural America,” Burton said. “That mission was accomplished with flying colors, but as society changed, that changed.”

Communities voted on school districts with which they wanted to consolidate. Much like an election year, people went door to door trying to sell their neighbors on a particular district.

As the schoolhouses closed, some were sold at auction, turned into barns, moved, destroyed or abandoned.

But as Burton has worked on this over the years, he’s found an increasing number of people are realizing the importance of preserving what history is left, which is heartening.

For example, Texas County has a historic driving tour of one-room schoolhouses.

“There seems to be a resurgence of interest in preserving the one-room schoolhouse,” he said. “That’s encouraging. There’s a lot that can be learned from the older generation about community, family and what it meant to be educated in a one-room schoolhouse. This has been a fun project.”

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

I Am From

A poem I worked on about a year ago following the now famous "where I'm from" formula for personal poems. Thought I'd share it.

I AM FROM

by David L. Burton

I AM FROM

by David L. Burton

I am from rugged gardeners and canners,

Frugal land rich, cash poor farmers,

Close-knit Scotch-Irish and British immigrant families

Quiet readers, English teachers, insurance adjusters and auto

mechanics.

I am from the rocky fields and rolling hills of the Ozarks

Shallow clear rivers with Indian names and catfish ponds,

Blonde brick ranch houses, and white clap-board bungalows,

Winding country roads and limestone glades that jut out of fescue

fields

I am from habits formed during the good ole days,

in cramped one-room schools, amid fears of another depression,

in a mostly-white region known for high school sports teams

bluegrass music, thousands of churches and Silver Dollar City.

I am from stubborn, independent, Christian, hardworking good folk

Fried chicken, green beans, mashed potatoes with white gravy,

apple pie a la mode, black coffee, homegrown mint and

peanut butter chocolate chip cookies made by the knotted hands of

my grandma.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Limited Time Offer

I've been working on some stories and poems for entry in the annual Springfield Writer's Guild contest. I've got four stories ready to go and two poems. My children are readers of my final content and I appreciate their input, even though they didn't like three of my four short stories!

One writing they did like was my poem, "Limited Time Offer." It is eight stanzas (I'm only going to share two here today) and it was inspired by a single statement made during a church service at Ridgecrest Baptist Church in Springfield, Mo. about six months ago. I wrote it down at the time and thought "that would make a great song."

Well, I'm not a song writer -- and probably not much of a poet either -- but here is what I've done with it so far. I'd like to know what you think of it.

One writing they did like was my poem, "Limited Time Offer." It is eight stanzas (I'm only going to share two here today) and it was inspired by a single statement made during a church service at Ridgecrest Baptist Church in Springfield, Mo. about six months ago. I wrote it down at the time and thought "that would make a great song."

Well, I'm not a song writer -- and probably not much of a poet either -- but here is what I've done with it so far. I'd like to know what you think of it.

Limited Time Offer

A

line of people wrapped around the store.

A

black Friday sell off of goodies galore.

The

doors opened and people rushed in

Racing

around with money to spend.

This

seasonal chance to fill coffers

Really

is a limited time offer.

Every

human on this Earth

Can

accept God’s new birth.

But

unlike Black Friday deals,

Limited

engagements and QVC appeals,

Rejecting

this offer will only bring sorrow

Since

no one has the guarantee of a tomorrow.

Friday, August 09, 2013

Books Focused on History of One-Room Schools in the Ozarks are Now Available Online

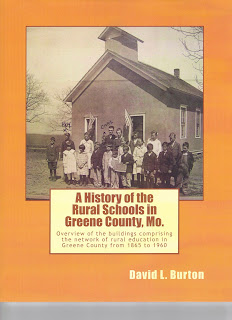

SPRINGFIELD, Mo. – Two books focused on

one-room schools in Missouri -- “A History of the Rural Schools in Greene

County, Mo.” and “Driving Tour of One-Room Schools in the Ozarks” -- are now

available for purchase online. Both written by David L. Burton and can be

purchased from Amazon.com or Createspace.com in either printed and digital

formats.

For nearly 10 years, the only way to get

a copy of these books had been to visit the Greene County Extension Center in

Springfield, Mo.

GREENE

COUNTY SCHOOLS

Over

1,000 copies of the book about rural schools in Greene County been sold since its

first release in 2000. Since 2002, proceeds from the sale of this book have

gone to the Greene County Extension Center.

"The

one-room school is the foundation of public education and a reflection of

Missouri's spirit and character. These books capture that spirit, details the

rise and fall of one-room schools in this county, and encourages this type of

historical community development elsewhere," said Burton.

This book

includes a catalog listing of every one-room school in the county with special

attention given to the buildings that are still standing.

OZARKS SCHOOL

TOUR

With

the book “Driving Tour of One-Room Schools in the Ozarks,” local history

enthusiasts can take a 200- mile, six-hour driving tour and see most of the

remaining one-room rural schools houses in Greene County. The self-guided

driving tour provides detailed directions as well as a photo of each school and

basic information about the structure.

This book also

includes addresses and information on 21 other one-room schools located in the

Ozarks outside of Greene County.

“I get inquiries

from folks wanting to see some of the rural schools in this county,” said

Burton. “This driving tour is the easiest way for folks to get to see most of

the schools. The schools on the tour are in a variety of conditions. Some

remain in use as community centers. Others have been converted into homes,

barns and even businesses.

ORDERING BOOK

“A

History of Rural Schools in Greene County, Mo” (priced at $15.99) and “Driving

Tour of One-Room Schools in the Ozarks,” (priced at $8.99) are written by David

L. Burton and are available at www.createspace.com and www.amazon.com.

Burton

is also available for public speaking on the topic of one-room schools in the

Ozarks. Contact him at the Greene County Extension Center at 417-881-8909.

There is a speaking fee of $35 payable to Greene County Extension.

Thursday, August 08, 2013

Comments about my three new books are coming in on Facebook and by email. Here are two recent examples.

In reference to "A History of Rural Schools in Greene County, Mo.," Scott Jones wrote: "David, I ordered mine when I read about this on your FB page, it was delivered on Friday. I'm lovin' it! I'm passing it on to my grandmother (90), she is a Greene County native, and attended Center. If you do an update, let me know---we've got some pictures!"

In reference to "Prayers for my Public School," Alice B wrote: "David, I'm so glad you put this in book form. I've followed the Facebook page for two years and it has been such a blessing. Having this in book form makes it easier to use during my Bible study and perhaps even share with others. This new book is a blessing and it looks fantastic!"

Thanks for the kind words. Keep spreading the word about the books.

In reference to "A History of Rural Schools in Greene County, Mo.," Scott Jones wrote: "David, I ordered mine when I read about this on your FB page, it was delivered on Friday. I'm lovin' it! I'm passing it on to my grandmother (90), she is a Greene County native, and attended Center. If you do an update, let me know---we've got some pictures!"

In reference to "Prayers for my Public School," Alice B wrote: "David, I'm so glad you put this in book form. I've followed the Facebook page for two years and it has been such a blessing. Having this in book form makes it easier to use during my Bible study and perhaps even share with others. This new book is a blessing and it looks fantastic!"

Thanks for the kind words. Keep spreading the word about the books.